How to train an AI-enabled workforce — and why you need to

Artificial intelligence (AI) is taking the business world by storm, with at least three in four organizations adopting the technology or piloting it to increase productivity.

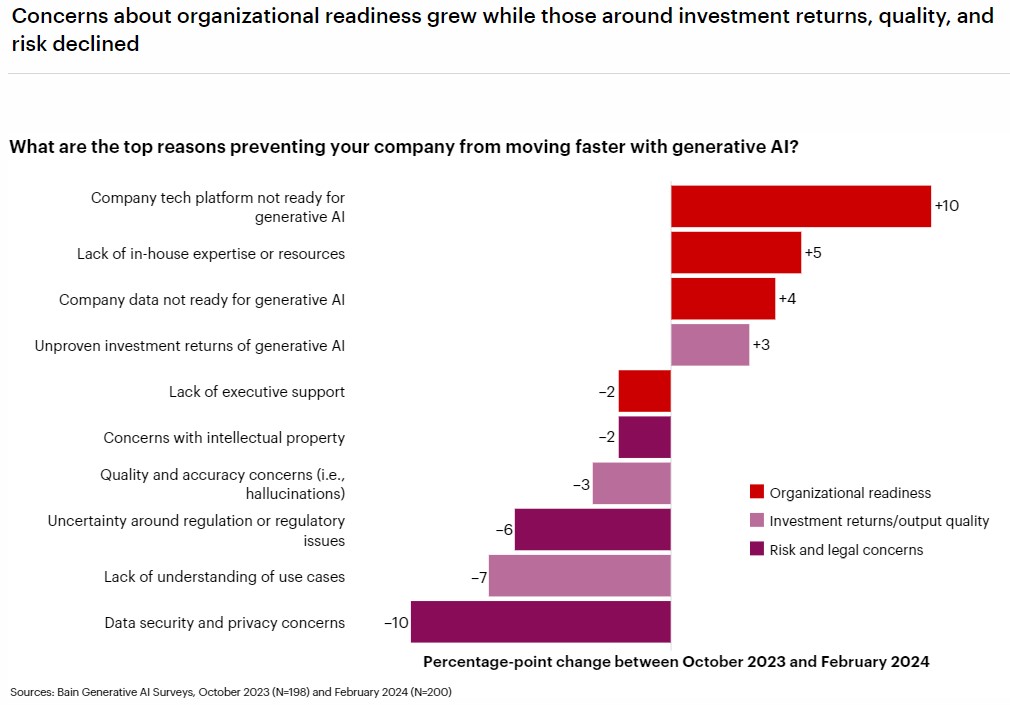

Over the next two years, generative AI (genAI) will force organizations to address a myriad of fast-evolving issues, from data security to tech review boards, new services, and — most importantly — employee upskilling.

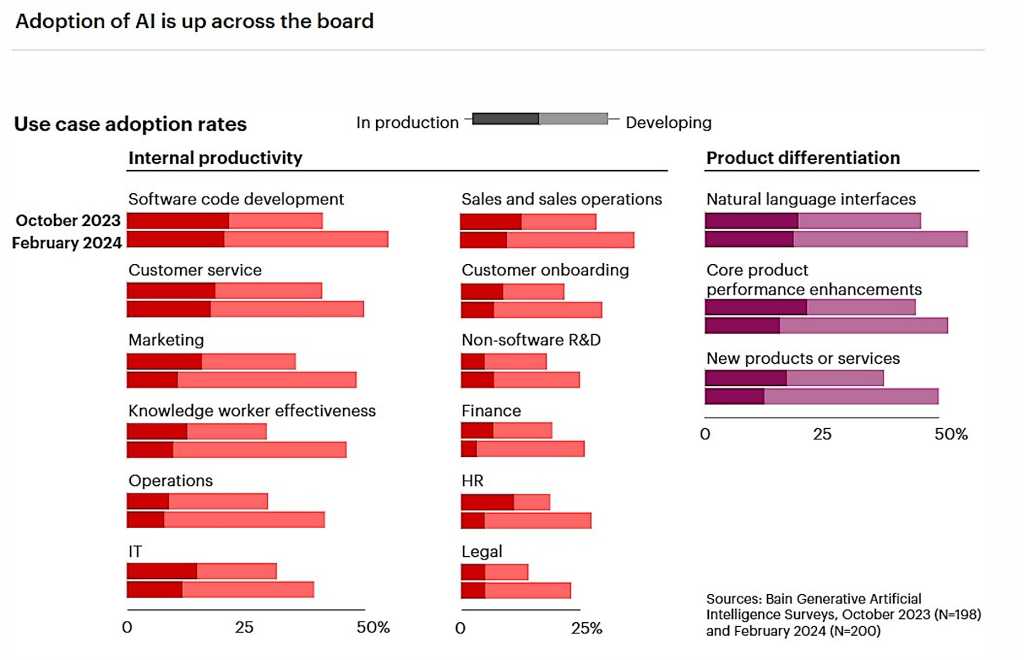

At the beginning of this year, 87% of 200 companies surveyed by Bain & Co., a management consulting firm, said they were already developing, piloting, or had deployed genAI in some capacity. Most of the early rollouts involved tools for software code development, customer service, marketing and sales, and product differentiation.

Companies are investing heavily in the technology — on average, about $5 million annually with an average of 100 employees dedicating at least some of their time to genAI. Among large companies, about 20% are investing up to $50 million per year, according to Bain & Co.

By 2027, genAI will represent 29% of organizational AI spending, according to IDC. In all, the AI market is projected to be valued at $407 billion by 2027.

“The way I often describe this is AI is sucking the air out of almost all non-AI investments in the whole tech world,” said Harvard Business School Professor David Yoffie.

As adoption soars, companies are struggling to hire people with much-needed AI knowledge and experience. Many are even cutting what they believe are unnecessary jobs and replacing them with AI-skilled workers, though the majority of organizations aren’t replacing employees, they’re retraining them.

A recent survey at business consultancy Heidrick & Struggles showed a 9% year-over-year rise in companies developing AI talent internally.

Bain & Co.

Not yet ready for adoption

Tech services provider AND Digital recently published its CEO Digital Divide report based on a survey in April among 500 UK respondents, 50 in the US and 50 in the Netherlands; it found 76% of respondents had already launched AI boot camps, even as 44% also said their staff remained unready for AI adoption.

“Our research indicates that fear of falling behind is a major driver behind this trend,” AND Digital said in the report. “Fifty-five percent of respondents told us that the pace at which new technologies are emerging is causing alarm among the senior leadership team.”

Emily Rose McRae, a Gartner senior director analyst, said 18 months ago she would have recommended organizations delay upskilling workers on genAI until they had specific use cases. Now, McRae sees workers using genAI behind the scenes — even at organizations that have banned it.

“If employees are using genAI despite bans, then organizations need to make sure their workforce understands the risks and realities of the tools,” McRae said. “A general genAI training should also include a clear discussion of potential risks, and why review of content produced by genAI is critical, even for interim internal content such as memo or email drafts.”

The poll by AND Digital also showed 62% of CEOs think moving too slowly to adopt AI is riskier than moving too fast. “Shockingly, 43% said they believe AI could replace the job of the CEO, underlining the widespread fears that the technology could destroy traditional job roles,” the report stated.

Experts don’t believe AI tools will replace workers; they envision workers who understand how to apply AI in their current positions will replace those who don’t. In fact, two-thirds of current occupations could be partially automated by AI, according to Goldman Sachs.

AI centric-training is needed

Building an AI team is an evolving process, just as genAI itself is steadily evolving — even week to week. “First, it’s crucial to understand what the organization wants to do with AI,” Corey Hynes, executive chair and founder at IT training company Skillable, said in an earlier interview with Computerworld.

“Second, there must be an appetite for innovation and dedication to it, and a strategy — don’t embark on AI efforts without due investment and thought. Once you understand the purpose and goal, then you look for the right team,” Hynes added.

Building an AI team is an evolving process, just as genAI itself is steadily evolving. Some of the top roles companies might need:

• A data scientist who can simplify and navigate complex datasets and whose insights provide useful information as AI models are built.

• An AI software engineer who often owns design, integration, and execution of machine-learning models into systems.

• A chief AI officer (CAIO) or leader to provide leadership and guidance in implementing and leading AI initiatives to ensure alignment and execution.

• An AI security officer to handle the unique challenges, such as ensuring adherence to regulations, data transparency, and internal vulnerabilities that come with AI models and algorithms, including adversarial attacks, model bias, and data poisoning.

• Prompt engineers who can craft and improve text queries or instructions (prompts) in large language models (LLMs) to get the best possible answers from genAI tools.

• Legal consultants to advise IT teams to ensure organizations abide by regulations and laws.

There are practical methods for building AI expertise in an organization, including training programs and career development initiatives to drive innovation and maintain a competitive edge.

Bain & Co.

Rethinking the workforce in terms of AI tools

“You’re seeing organizations thinking about their workforce in different ways than five or 10 years ago,” said Gustavo Alba, Global Managing Partner for Technology & Services Practice at Heidrick & Struggles, an international executive search and management consulting company.

Corporate AI initiatives, Alba said, are similar to the shift that took place when the internet or cloud computing took hold, and there was “a sudden upskilling” in the name of productivity. Major technology market shifts also affect how employees think about their careers.

“Am I getting the right development opportunities from my employer? Am I being upskilled?” Alba said. “How upfront are we about leveraging some of these innovations? Am I using a private LLM at my employer? If not, am I using some of the public tools, i.e. OpenAI and ChatGPT? How much on the cutting edge am I getting and how much are we innovating?”

Companies that aren’t upskilling their workforce not only face falling behind in productivity and innovation, they could lose employees. “I think you have a workforce looking at [genAI], and asking, ‘What is my organization doing and how forward looking are they?”

When it comes to upskilling workers for the AI revolution, Alba said, workers can fall into one of three basic archetypes:

- AI technology creators, or those highly skilled employees who work at AI start-ups and stalwarts such as Amazon, OpenAI, Cohere, Google Cloud and Microsoft. They are a relatively small pool of employees.

- Technologists who understand technology in general, i.e. CTOs, software developers, IT support specialists, network and cloud architects, and security managers. They may understand traditional technology, but not necessarily AI, and represent a larger pool of employees.

- Workers who perform non-technical tasks but who can become more productive and efficient through the use of AI. For example, understanding how Zoom can use AI to summarize an online meeting into bullet points.

AI technology creators require no additional training. Technologists are relatively easy to train on AI, and they’ll catch onto its potential quickly (such as software developers using it to help generate new code). But the general workforce will require more care and handling to understand the full potential of AI.

Alba believes every employee should receive some training on AI, but the exact type depends on their job. The quality of work and the amount of work that can be accomplished by an employee using AI compared to one who doesn’t can provide a competitive advantage, he noted.

“When was the last time we said that about a technology: that an end-user goes off and figures out how to apply it to their workflow,” Alba said. “All of a sudden, we’re discovering on an individual basis how to use these tools, but imagine an organization being in the forefront and saying, ‘I can suddenly get three times more productivity and increase quality or an investment of X.’”

For example, a customer care organization could train its employees on how to use Microsoft Copilot, which can come as part of Office 365. Representatives can then feed customer queries into Copilot and obtain the most appropriate responses in seconds. Chatbots like Copilot can also generate high-level reports. For example, a user could produce a list of top customer issues over the past quarter to be used to improve service.

“You can imagine getting trained up around an agent on how and when to respond with intuitive messaging, especially if it comes to you in writing,” Alba said. “You can also imagine a world where a chatbot takes all those [past customer patterns and purchases] and then helps guide the conversation with them.”

GenAI training vs. real-world use

While many organizations offer some basic training on genAI, it’s not really doing much to increase adoption or deliver the productivity gains “that genAI was hyped to provide,” according to Gartner’s McRae. “This is particularly true if the organization has a generic genAI tool that is available to everyone in the organization, as opposed to tools embedded within role-specific software employees already use on a day-to-day basis.”

Training that’s not followed with on-the-job use is “wasted training,” McRae said, because workers still don’t have clarity on how it will apply in their workflow.

On-the-job application is particularly necessary because genAI use cases can be extremely broad and the learning curve too high for creating prompts that achieve usable results. It takes time and iteration, according to McRae.

“It’s not a fully generalizable skill — because each tool has different fine-tuning and on of a variety of LLMs underlying them, prompt engineering techniques that work with one tool may not work with another. [That] means a lot of iteration, even for experienced genAI prompt writers,” she said.

McCrae suggests companies include use cases and examples that not only demonstrate how the organization wants employees to use genAI, but also spells out the corporate philosophy about the technology. And it’s important to make clear what impact genAI will have on roles and workflows.

“For example, it could include sharing how genAI was used to develop first drafts of software programs, and software developers were assigned new workflows or roles that involved extensive review and testing of the GenAI-produced drafts,” McRae said. “Meanwhile, the organization was able to move people interested in software development — but without much experience in the field — into prompt engineering roles where they create the prompts to generate the first drafts of the software programs.”

Because of the risks associated with genAI hallucinations, and the fact that even if employees aren’t using genAI tools themselves they will be receiving content that has been produced using the technology, McRae recommends annual training on “Information Skepticism.”

“Information Skepticism training will be similar to how most organizations have an annual training on phishing followed by unannounced tests that direct any users who fail to remedial training, in order to manage information security risk,” she said.

Information Skepticism training should also be followed by followed by random tests to ensure employees are staying aware and vigilant of the risks, McRae said.

Heidrick & Struggles’s Alba believes the more hands-on employees get, the better — even beyond any bootcamps or courses academia can offer. He compared education on genAI to learning the possibilities of the Internet in the mid-1990s, saying it’s a new frontier and most organizations will have to “roll up their sleeves” and try out the tech to see where productivity gains lie.

“The reality is the academic part of it is interesting, but these are new models that we don’t even know what they can do yet,” Alba said. “I don’t think the educational institutions will catch up to the hands-on reality of playing around with these.”